A GoPride Interview

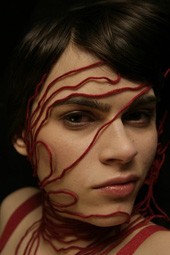

Kaki King

Kaki King interview with ChicagoPride.com

Wed. August 16, 2006 by ChicagoPride.com

Kaki King may have earned her musical reputation as a supernaturally-talented acoustic guitar player, but you’ll never be able to pigeon-hole her as just some strum-happy guitar virtuoso. King also happens to be an out-loud and proud lesbian, but she bristles at the thought of being called a "gay musician."

Both bad-ass and demure, fiercely intelligent and playfully silly, King is an artist who instinctively wriggles free from the confining boundaries of any reductive label. And that includes any static interpretations of her own music. She may give listeners teasing hints about what her songs are about, but she’d rather have fans interpret her work to suit their own emotional needs.

Though she won vast critical acclaim—not to mention spots on Letterman and Conan O’Brien--with her first two releases, the instrumental acoustic albums Everybody Loves You (2003) and Legs to Make Us Longer (2004), King brazenly transcends the limitations of her former genre with her new album ...Until We Felt Red. An emotional song cycle that is louder, lusher, and more vibrantly hued than anything she has done in the past, Red showcases King at play amidst an exhilarating instrumental array, including buzzing electric guitar, bashing drums, twangy lap steel, majestic trumpet, and the techno sounds of various bleeps, loops, and samples. King has also added the sound of her own voice to a few songs, using her girlish instrument to big effect on lyrics that touch on such disparate topics as nuclear warfare and her first lesbian affair.

Produced by John McEntire (Tortoise, Stereolab, Sea & Cake), ...Until We Felt Red reveals a mind—and a talent—that is constantly on the move--searching, challenging, questioning. On the eve of the album’s August 8th release on Velour Records, King exhibited a similar vigorousness during an interview that touched upon such topics as her musical evolution, her coming-out experience, and her thoughts on gay marriage.

CP: When did you know that you were gay?

KK: I had figured out by about age 14 that being gay was something I was going to need to think about later on in my life. I was dating boys at the time, so I thought, "I’ll just deal with this later!" Then my parents ended up finding out through a letter I had written to a girl at summer camp, but then it became something we really didn’t discuss. It’s a pretty typical story.

CP: When did you feel like you started living openly as a gay person?

KK: In college, I guess. My high school was in the South, and it was very conservative. It was a Christian high school, and I didn’t fit in there to begin with. I was one of the only girls who had short hair. I didn’t have a butch haircut—I just had a short little pixie haircut. I mean, it was a really a Stepford Wives kind of vibe.

I’m sure that everyone has blossomed into being fabulous people [laughs], but at the time, it was like, “This is just not worth it to try to be openly gay. They just won’t get it.’

CP: Tell me about when you first started playing guitar?

KK: I started playing when I was five. My parents thought children should take music lessons, and it was probably my dad's decision that guitar would be my instrument.

CP: Interesting. What about the more feminine piano?

KK: I did take some piano lessons, and I actually didn’t like playing the guitar at all. It was a very difficult instrument to play when you’re that young.

I only ended taking lessons for that first year, until I was six years old. But my father just kept a guitar around the house—he played a little, too—and because it was always there, and I developed a love for music at an early age, I just kept learning and playing over time.

CP: When did you start liking it?

KK: When all the boys started playing—maybe around age nine or ten. They started getting their first guitars, but I could already play. So they thought I was really cool. It’s funny because although I’m a lesbian, I’ve always really appreciated the attention of men. I’ve always sort of sought it out. I don’t know what that means! [laughs] Maybe because I feel like that I’m one of them.

CP: At the risk of sounding like an amateur psychoanalyst—

KK: Go ahead.

CP: It must have something to do with your father as well. I mean, he is the one who put the guitar in your hand.

KK: Yeah, he and I shared music. He is more of my best musical buddy than my dad who I go to for sound advice. That’s my mom—my mom is like my MOM! My dad is my guy. My mother is a very amazing and creative in her own way, but she is more of a business woman. She started a law firm and urged my father to go to law school. She’s really really brilliant, and she runs the show, while my dad kind of took over the artistic role in the family.

CP: When did you feel like music was something you were going to do with you life?

KK: Well, at NYU, I was in a division where you create your own major. It was great, and I tried to focus on music, but I ended up doing a lot of different things. I realized that if I was going to go somewhere in life with a degree that was relevant, I was going to have to go to graduate school. So, I finished up my undergraduate work in 3 years and took a year off to figure out what kind of graduate school I wanted to attend. It also provided me the opportunity to live in New York and just work and have a good time. It was during that year off that I decided to give it a try as a musician.

I had no delusions of grandeur about being a success, because instrumental acoustic guitar music hadn't had any commercial success since the 80's.

Even after the release of my first album I had an in-town gig playing in the band for Blue Man Group.

You know, you have to reach a certain point of financial security before you say, "This is definitely what I want to be doing, and it’s not going to go away tomorrow."

CP: Have you ever felt pressure from anyone in the music business to keep quiet about being a lesbian?

KK: No. I do as I please, I wear what I want. But I have to say, the way I look doesn’t particularly spell “stereotypical lesbian” the second you see me, especially when I’m all dolled up in a photo. But I would say that had that not been the case, some people probably would have wanted to fem me up a bit. I don’t know.

CP: You mean your package was already fem enough?

KK: Apparently. And no one was trying to market me to a mainstream crowd, so there was none of that pressure. But I definitely know of other artists—both gay and straight--who have have been pressured to be something they’re not. Ultimately, I don’t think the fact that I’m gay has had all that much impact on my career as a musician, good or bad. I don’t know if anyone really cares that I’m a lesbian. Liking a musicain just because they’re gay is ultimately a superficial reason. It’s like buying a record because a singer is dating some Hollywood star. To be honest, I never really think about it. It’s not something that I have to protect or be dishonest about it.

CP: I have a close female relative who recently came out of the closet at sixteen years old, and my family didn’t really blink an eye. Do you think it’s easier for young people to be openly gay at an earlier age these days?

KK: I definitely think my generation has things a lot of easier in terms of being out in the world. It didn’t come at a price for us, but it did come at a price for a lot of people who are older than us. And I’m talking about people who are only five or ten years older. I can see a change in the attitude of some of my relatives even in the last decade.

Now they are so much more comfortable with my being gay because it has become more culturally visible and acceptable. Things like the Will & Grace phenomenon have definitely helped people become more accepting. I do appreciate that it was not always like that for older gay men and lesbians and that it is still very difficult for some gay people to be who they are.

CP: Have you ever been personally discriminated against because you were gay?

KK: You know, I’ve lived my entire gay life in New York, and it’s been so easy. I’ve never lived anywhere else as a gay person. But I’ll tell you, the day I’m turned down to buy a house or get a loan because I’m gay, I would be so outraged I'd have the ACLU on the phone within minutes. So, as far as my personal experience goes, I’m a little naïve about what gay people struggle through. That said, I do know people who are closeted because they’re afraid they will lose their jobs. I think it’s terrible that that’s the way it is. I do hate to say I live in a bubble—being a musician, you already live in a bubble—but when you start to think about what goes on it some parts of this country and in the rest of the world, it’s really awful.

CP: Let’s talk about the music for a bit. Up until this record, you have been primarily known for your amazingly accomplished instrumental acoustic guitar work. Do you feel that your emotions and creativity are best expressed through this form of music?

KK: No, I wouldn’t say that. It’s a very small genre of music, but I happened to grow up with it because my father enjoyed this whole guitar idiom. For me, instrumental acoustic guitar was a discipline that I really enjoyed--it was just one of the things I did musically, and I happened to make two records of instrumental acoustic guitar music. But now I’ve made a third album which is still mostly instrumental, but definitely not in the acoustic idiom any longer because I was tired of it. I felt like I was being limited by my choice of instrumentation.

It’s so hard to have just one thing sum up the entirety of your creative life. After a certain point, I was eager to break away from the limitations of the acoustic guitar and to do larger songs with bigger instrumentation and sounds.

CP: Is it a much different approach for you when you are composing a song with lyrics and vocals versus one that is purely instrumental?

KK: There is a big difference. I mean, there are songwriters who are amazing at writing songs with lyrics for vocalists. I’m certainly not one of them. So, for me, it’s about using the voice as an instrument. And I think a lot about the lyrics I write, even though most people may not be able to understand them. It’s not your typical song with vocals.

CP: Speaking of songs with lyrics, tell me about "Jessica," which was written about one of your early lesbian experiences.

KK: I wrote that a long time ago. I was about fifteen or sixteen. It sounds like I’m pining away for this woman, but in reality, she's the one waiting for me. She was this 21-year-old teacher’s assistant at this nerd camp that I went to during the summer. We had fun together. But she was very interested in me, and I was very interested in my sexuality and not necessarily her. But when people hear the song, they say, "Oh, you must have really been in love with her." No, she was after me [laughs], and I just wrote this song. Ultimately, the song is probably about trying to remember a love that never really was.

CP: But do you feel like she had a major influence on you, even if it was just by being in your orbit at a really formative time?

KK: Sure. I mean that was the first summer that I kissed a girl, and she was this strange influence because she was older, and she was interested in me.

CP: Tell me about the song "Gay Sons of Lesbian Mothers." It’s an instrumental track, and it’s the most electronic song on the album.

KK: I was going to put in paretheses, after the title, "Shit Happens." [laughs] There’s really not much more to it than that.

CP: Was there a specific gay son of a lesbian mother?

KK: I’m sure there was. It’s really me wondering if that particular family dynamic makes life more complicated.

CP: And the fact that it’s an electronic track—was that a conscious nod to gay club culture?

KK: I don’t think so. I’m sure that people will pull that out—that it sounds the gayest song on the album. Or the gay boy-est on the album. Then I’ll have to figure out what the gay girl-est song on the album is. I guess that would have to be "Yellowcake." The irony is that to a lot of people, “Yellowcake” sounds light and happy and feminine, but it’s actually so weird and so dark.

CP: Well, there’s definitely some darkness on this record.

KK: Oh, a lot.

CP: But what I’m also discovering, after talking to you, is that even in the instrumental tracks, there is also a lot of irony. You’re very mischievous that way. It’s almost like saying, "Like can be very dark, but let’s laugh about it."

KK: That’s the irony of modern life. You go into therapy to become happier, but then there’s all this suffering around you. So then, you think, "Perhaps I’m just in denial.

I seem happy-go-lucky, but maybe I'm just ignoring the reality of what’s out there." Then, you have to go back into therapy! [laughs]

CP: Last topic. Do you see yourself getting married someday?

KK: You know, it’s having that choice to get married that’s important for gay people. Personally, I don’t believe in God, and I don’t believe that anyone needs to sanctify my relationship. But at some point, I think marriage might become a very practical stage in a relationship for me, so yeah, I might get married someday. No ceremony, though, but I like having parties [laughs], so I’m going to throw a big one!

Both bad-ass and demure, fiercely intelligent and playfully silly, King is an artist who instinctively wriggles free from the confining boundaries of any reductive label. And that includes any static interpretations of her own music. She may give listeners teasing hints about what her songs are about, but she’d rather have fans interpret her work to suit their own emotional needs.

Though she won vast critical acclaim—not to mention spots on Letterman and Conan O’Brien--with her first two releases, the instrumental acoustic albums Everybody Loves You (2003) and Legs to Make Us Longer (2004), King brazenly transcends the limitations of her former genre with her new album ...Until We Felt Red. An emotional song cycle that is louder, lusher, and more vibrantly hued than anything she has done in the past, Red showcases King at play amidst an exhilarating instrumental array, including buzzing electric guitar, bashing drums, twangy lap steel, majestic trumpet, and the techno sounds of various bleeps, loops, and samples. King has also added the sound of her own voice to a few songs, using her girlish instrument to big effect on lyrics that touch on such disparate topics as nuclear warfare and her first lesbian affair.

Produced by John McEntire (Tortoise, Stereolab, Sea & Cake), ...Until We Felt Red reveals a mind—and a talent—that is constantly on the move--searching, challenging, questioning. On the eve of the album’s August 8th release on Velour Records, King exhibited a similar vigorousness during an interview that touched upon such topics as her musical evolution, her coming-out experience, and her thoughts on gay marriage.

CP: When did you know that you were gay?

KK: I had figured out by about age 14 that being gay was something I was going to need to think about later on in my life. I was dating boys at the time, so I thought, "I’ll just deal with this later!" Then my parents ended up finding out through a letter I had written to a girl at summer camp, but then it became something we really didn’t discuss. It’s a pretty typical story.

CP: When did you feel like you started living openly as a gay person?

KK: In college, I guess. My high school was in the South, and it was very conservative. It was a Christian high school, and I didn’t fit in there to begin with. I was one of the only girls who had short hair. I didn’t have a butch haircut—I just had a short little pixie haircut. I mean, it was a really a Stepford Wives kind of vibe.

I’m sure that everyone has blossomed into being fabulous people [laughs], but at the time, it was like, “This is just not worth it to try to be openly gay. They just won’t get it.’

CP: Tell me about when you first started playing guitar?

KK: I started playing when I was five. My parents thought children should take music lessons, and it was probably my dad's decision that guitar would be my instrument.

CP: Interesting. What about the more feminine piano?

KK: I did take some piano lessons, and I actually didn’t like playing the guitar at all. It was a very difficult instrument to play when you’re that young.

I only ended taking lessons for that first year, until I was six years old. But my father just kept a guitar around the house—he played a little, too—and because it was always there, and I developed a love for music at an early age, I just kept learning and playing over time.

CP: When did you start liking it?

KK: When all the boys started playing—maybe around age nine or ten. They started getting their first guitars, but I could already play. So they thought I was really cool. It’s funny because although I’m a lesbian, I’ve always really appreciated the attention of men. I’ve always sort of sought it out. I don’t know what that means! [laughs] Maybe because I feel like that I’m one of them.

CP: At the risk of sounding like an amateur psychoanalyst—

KK: Go ahead.

CP: It must have something to do with your father as well. I mean, he is the one who put the guitar in your hand.

KK: Yeah, he and I shared music. He is more of my best musical buddy than my dad who I go to for sound advice. That’s my mom—my mom is like my MOM! My dad is my guy. My mother is a very amazing and creative in her own way, but she is more of a business woman. She started a law firm and urged my father to go to law school. She’s really really brilliant, and she runs the show, while my dad kind of took over the artistic role in the family.

CP: When did you feel like music was something you were going to do with you life?

KK: Well, at NYU, I was in a division where you create your own major. It was great, and I tried to focus on music, but I ended up doing a lot of different things. I realized that if I was going to go somewhere in life with a degree that was relevant, I was going to have to go to graduate school. So, I finished up my undergraduate work in 3 years and took a year off to figure out what kind of graduate school I wanted to attend. It also provided me the opportunity to live in New York and just work and have a good time. It was during that year off that I decided to give it a try as a musician.

I had no delusions of grandeur about being a success, because instrumental acoustic guitar music hadn't had any commercial success since the 80's.

Even after the release of my first album I had an in-town gig playing in the band for Blue Man Group.

You know, you have to reach a certain point of financial security before you say, "This is definitely what I want to be doing, and it’s not going to go away tomorrow."

CP: Have you ever felt pressure from anyone in the music business to keep quiet about being a lesbian?

KK: No. I do as I please, I wear what I want. But I have to say, the way I look doesn’t particularly spell “stereotypical lesbian” the second you see me, especially when I’m all dolled up in a photo. But I would say that had that not been the case, some people probably would have wanted to fem me up a bit. I don’t know.

CP: You mean your package was already fem enough?

KK: Apparently. And no one was trying to market me to a mainstream crowd, so there was none of that pressure. But I definitely know of other artists—both gay and straight--who have have been pressured to be something they’re not. Ultimately, I don’t think the fact that I’m gay has had all that much impact on my career as a musician, good or bad. I don’t know if anyone really cares that I’m a lesbian. Liking a musicain just because they’re gay is ultimately a superficial reason. It’s like buying a record because a singer is dating some Hollywood star. To be honest, I never really think about it. It’s not something that I have to protect or be dishonest about it.

CP: I have a close female relative who recently came out of the closet at sixteen years old, and my family didn’t really blink an eye. Do you think it’s easier for young people to be openly gay at an earlier age these days?

KK: I definitely think my generation has things a lot of easier in terms of being out in the world. It didn’t come at a price for us, but it did come at a price for a lot of people who are older than us. And I’m talking about people who are only five or ten years older. I can see a change in the attitude of some of my relatives even in the last decade.

Now they are so much more comfortable with my being gay because it has become more culturally visible and acceptable. Things like the Will & Grace phenomenon have definitely helped people become more accepting. I do appreciate that it was not always like that for older gay men and lesbians and that it is still very difficult for some gay people to be who they are.

CP: Have you ever been personally discriminated against because you were gay?

KK: You know, I’ve lived my entire gay life in New York, and it’s been so easy. I’ve never lived anywhere else as a gay person. But I’ll tell you, the day I’m turned down to buy a house or get a loan because I’m gay, I would be so outraged I'd have the ACLU on the phone within minutes. So, as far as my personal experience goes, I’m a little naïve about what gay people struggle through. That said, I do know people who are closeted because they’re afraid they will lose their jobs. I think it’s terrible that that’s the way it is. I do hate to say I live in a bubble—being a musician, you already live in a bubble—but when you start to think about what goes on it some parts of this country and in the rest of the world, it’s really awful.

CP: Let’s talk about the music for a bit. Up until this record, you have been primarily known for your amazingly accomplished instrumental acoustic guitar work. Do you feel that your emotions and creativity are best expressed through this form of music?

KK: No, I wouldn’t say that. It’s a very small genre of music, but I happened to grow up with it because my father enjoyed this whole guitar idiom. For me, instrumental acoustic guitar was a discipline that I really enjoyed--it was just one of the things I did musically, and I happened to make two records of instrumental acoustic guitar music. But now I’ve made a third album which is still mostly instrumental, but definitely not in the acoustic idiom any longer because I was tired of it. I felt like I was being limited by my choice of instrumentation.

It’s so hard to have just one thing sum up the entirety of your creative life. After a certain point, I was eager to break away from the limitations of the acoustic guitar and to do larger songs with bigger instrumentation and sounds.

CP: Is it a much different approach for you when you are composing a song with lyrics and vocals versus one that is purely instrumental?

KK: There is a big difference. I mean, there are songwriters who are amazing at writing songs with lyrics for vocalists. I’m certainly not one of them. So, for me, it’s about using the voice as an instrument. And I think a lot about the lyrics I write, even though most people may not be able to understand them. It’s not your typical song with vocals.

CP: Speaking of songs with lyrics, tell me about "Jessica," which was written about one of your early lesbian experiences.

KK: I wrote that a long time ago. I was about fifteen or sixteen. It sounds like I’m pining away for this woman, but in reality, she's the one waiting for me. She was this 21-year-old teacher’s assistant at this nerd camp that I went to during the summer. We had fun together. But she was very interested in me, and I was very interested in my sexuality and not necessarily her. But when people hear the song, they say, "Oh, you must have really been in love with her." No, she was after me [laughs], and I just wrote this song. Ultimately, the song is probably about trying to remember a love that never really was.

CP: But do you feel like she had a major influence on you, even if it was just by being in your orbit at a really formative time?

KK: Sure. I mean that was the first summer that I kissed a girl, and she was this strange influence because she was older, and she was interested in me.

CP: Tell me about the song "Gay Sons of Lesbian Mothers." It’s an instrumental track, and it’s the most electronic song on the album.

KK: I was going to put in paretheses, after the title, "Shit Happens." [laughs] There’s really not much more to it than that.

CP: Was there a specific gay son of a lesbian mother?

KK: I’m sure there was. It’s really me wondering if that particular family dynamic makes life more complicated.

CP: And the fact that it’s an electronic track—was that a conscious nod to gay club culture?

KK: I don’t think so. I’m sure that people will pull that out—that it sounds the gayest song on the album. Or the gay boy-est on the album. Then I’ll have to figure out what the gay girl-est song on the album is. I guess that would have to be "Yellowcake." The irony is that to a lot of people, “Yellowcake” sounds light and happy and feminine, but it’s actually so weird and so dark.

CP: Well, there’s definitely some darkness on this record.

KK: Oh, a lot.

CP: But what I’m also discovering, after talking to you, is that even in the instrumental tracks, there is also a lot of irony. You’re very mischievous that way. It’s almost like saying, "Like can be very dark, but let’s laugh about it."

KK: That’s the irony of modern life. You go into therapy to become happier, but then there’s all this suffering around you. So then, you think, "Perhaps I’m just in denial.

I seem happy-go-lucky, but maybe I'm just ignoring the reality of what’s out there." Then, you have to go back into therapy! [laughs]

CP: Last topic. Do you see yourself getting married someday?

KK: You know, it’s having that choice to get married that’s important for gay people. Personally, I don’t believe in God, and I don’t believe that anyone needs to sanctify my relationship. But at some point, I think marriage might become a very practical stage in a relationship for me, so yeah, I might get married someday. No ceremony, though, but I like having parties [laughs], so I’m going to throw a big one!

Interviewed by ChicagoPride.com