A GoPride Interview

Justin Hall

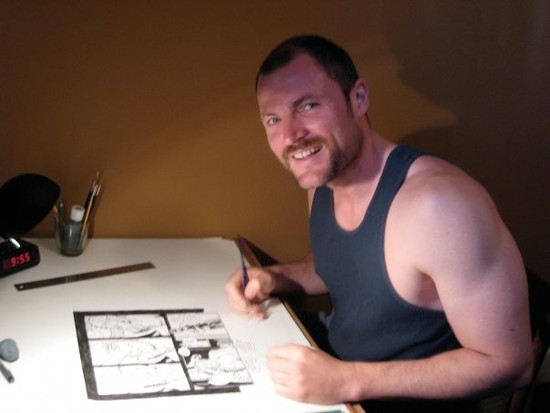

No straight line: Cartoonist and writer Justin Hall discusses his new work

Thu. July 19, 2012 by Danny Bernardo

In the past, if there was a comic with a queer character, it became a queer comic because the mainstream wouldn’t necessarily touch it.

Cartoonist and writer Justin Hall has been creating independent comics since 2001. The San-Francisco based creator of queer comic Glamazonia and author of the new book, No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics visited Chicago during Pride Weekend in June for a special event at Chicago Comics celebrating LGBT comic book creators, writers and artists. No Straight Lines is an intense labor of love, chronicling and archiving the rich heritage of queer work in the comics' world.

GoPride.com's Danny Bernardo caught up with Hall between the many LGBT panels he sat on during this year's Comic-Con and chatted about the impetus for the book and the intensive process of compiling this prolific work.

DB: (Danny Bernardo) What inspired you to collect this book?

JH: (Justin Hall) It actually started when I curated a museum show for the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco in 2006 called "No Straight Lines: Queer Culture in Comics." It was the first museum show of that kind of material, of LGBT comics. It went really well and I realized that there needed to be a book to gather all this work that's really in danger of being lost. This material was created in a separate universe parallel to the rest of the comic book world. It wasn't sold in comic book stores or bookstores but rather published by gay publishers, serialized in gay newspapers, and sold in gay bookstores. There have been a couple of creators who have been able to cross over to the mainstream, like Alison Bechdel (creator of Fun Home and Dykes to Watch Out For), but the vast majority of these comics are going to be lost even though a lot of it is very good. Even other cartoonists often don't know about queer comics because there were so isolated and removed from the traditional comic book world.

DB: You cover 4 decades, starting in the 70's. Was there anything that predated this decade that didn't make it into the book?

JH: I started the book at 1972 with Wimmen's Comix #1, with Trina Robbins writing about her roommate (who happened to be Robert Crumb's sister) in a story called "Sandy Comes Out." It was the first story about a queer person that was not a gag strip, not erotic comics, and not derogatory.

But really the first gay comics were gay male erotic comics. Tom of Finland was doing mail order distribution of his comics as early as the late 40's, I believe. A lot of erotic comics have been well archived by organizations like the Tom of Finland Foundation and The Center of Sex and Culture. My worry was that the literary queer comics were going to vanish, that there was no one looking out for that work. Especially with the gay publishers and the gay bookstores dying out.

DB: What were the challenges in compiling this historic archive?

JH: Certainly the fact that a lot of the material was out of print and that a lot of the creators were dead or had vanished was a challenge. Also, because there are so many different streams of this material; there was everything from the underground comix from the 70's, to the gay newspaper strips of the 80's, to the punk zines of the 90's, and now web comics. Each body of work required its own research process.

Luckily, I live in San Francisco where a lot of this material was developed. An old publisher of these comics, Last Gasp, is actually right around the corner from me. I was able to go through their warehouse and just rifle through and see what they had left. Also, a lot of the creators are around. Trina Robbins is my neighbor. I went up to Portland to talk to Andy Mangels and Robert Triptow who edited the Gay Comix anthology series. I've been doing a lot of work with Prism Comics, the non-profit advocacy group for LGBT comics, as their talent relations' chair, so I was lucky enough to have personal relationships with most of the people in the book.

We also have international work in the book, from Germany, Spain, France, Israel, some of which has been published for the first time in English. That material certainly presented obvious challenges. Looking forward, I'd love to do more about the web; that medium is exploding and opening up. It'd be wonderful to do a follow-up volume in five years with mostly queer webcomics.

DB: What has the response been like as it's just launched?

JH: A couple of weeks ago we did an advance debut in Chicago, we got some advance copies from the printer and it was the first time it was on sale. It actually hits the shelves in most places this week, the week of Comic-Con. The early buzz has been wonderful and gratifying. Everyone who has seen the book has been really positive about it. I've gotten push back here and there, of course. There was a blogger who was upset at the use of the word "queer;" he felt that it was a hate word. There are always going to be reactions like that.

Hopefully when the majority of people see this book, they'll be excited and hopefully amazed by the quality of this material. There's a lot of incredible stuff here that has escaped attention for too long.

DB: In compiling the material, was there anything you found that inspired you and your work?

JH: The bravery of the early queer comics is remarkable, and very inspiring. Mary Wings' Come Out Comix came out in 1973 and it's a pretty raw book. She told me she was 19 before she ever even heard the word "lesbian." She saw Trina's "Sandy Comes Out" soon after coming out herself and thought, "A straight woman shouldn't tell this story; it should be a lesbian." Then she made Come Out Comix in the basement of a radical women's karate co-operative and sold them for a $1 a piece by mail order. That takes some serious guts. Times have really changed, but at the same time you look back on the material from the 70's, from Wings and Roberta Gregory and others, then later coming out of the 80's with Howard Cruse and Gay Comix and that crew, and much of it is really brave, honest, and sophisticated.

I think now we're seeing similar work being done with trans identity. Christine Smith, for example, does a web comic called "The Princess" about a young trans girl. She's trying to show young trans kids that they're not pathological, that they're normal and can have happy lives in the same way that Mary Wings was trying to show young lesbians that they're normal and can have happy lives. It's a similar project across the generations and that's very inspiring.

Mind you, not everything in the book is celebratory stuff; it's also people looking at issues of racism in the queer community, the horrors of AIDS, partner abuse, all different kinds of things. There's some really powerful stuff and challenging stuff. The more I dug, that was what was most surprising, how many different points of view there were on queer realities.

DB: Speaking about generations, you've been in the queer comics scene for some time. How do you see the queer comic scene moving forward?

JH: The early battles were about basic visibility. Alison Bechdel talked about that when she created Dykes to Watch Out For; she just wanted to make lesbians visible. Twenty-five years later, that basic visibility isn't the issue any more. In a sense, that's the job of the mainstream comics industry now. The mainstream is including and assimilating queer characters, such as the gay Archie character and the lesbian Batwoman. But while it's now the mainstream's job to include and assimilate these characters, it remains the queer comics underground's job to continue to analyze and dissect and poke fun at queer identities in a way that is not appropriate for the mainstream to do. That needs to continue in the future.

Now that the traditional queer media ghetto of gay bookstores and gay newspapers is faltering, people who want to continue to make real niche material will find niche markets on the web. You can find audiences on the web in numbers that were unimaginable in the past.

At the same time, there's definitely more possibility for crossing over into the mainstream book market now.

There is more acceptance of graphic novels and the comic book form and certainly more acceptance of queer narratives.

DB: Why do you feel queer comics are important to the queer experience?

JH: Unlike film and television, which require a lot of money and collaboration and backing to do, comics is just you with ink and paper.

One person can create their own vision in queer comics and get it out there. That's really powerful. Queer comics tend to be quirkier, more challenging, and more ribald at times, because of their underground, DIY nature.

Another reason is that comics are a narrative form that's also visual; reading a comic about queer lives is different than just reading a book about queers. Young queers can look at it and can see themselves in it. And that's profound, that visceral interaction with a visual narrative.

DB: Why did you pick Chicago as the city for your advanced debut?

JH: This was the first year of CAKE (Chicago Alternative Comic Expo) and I wanted to have the book for the inaugural year. They were particularly interested in a good gender balance and queer inclusion for the show, which is something that a lot of people in the industry, even the independent comic industry, tend to gloss over. And when I found out Chicago Gay Pride was the next week, I decided to stay and do that event at Chicago Comics in Boystown. I had a great time in the city, did lots of cultural stuff. Saw Millennium Park, saw some theatre, including the hilarious Steamwerkz: the Musical. I had a blast; just walking the streets of Chicago was a blast. And not to be too gay here, but there are a lot of hot men in your fair city.

No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics hits the shelves at comic book stores this week, with a rollout at bookstores over the month. It is also available online at www.fantagraphics.com or you can stop into Chicago Comics, where it is currently in stock.

GoPride.com's Danny Bernardo caught up with Hall between the many LGBT panels he sat on during this year's Comic-Con and chatted about the impetus for the book and the intensive process of compiling this prolific work.

DB: (Danny Bernardo) What inspired you to collect this book?

JH: (Justin Hall) It actually started when I curated a museum show for the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco in 2006 called "No Straight Lines: Queer Culture in Comics." It was the first museum show of that kind of material, of LGBT comics. It went really well and I realized that there needed to be a book to gather all this work that's really in danger of being lost. This material was created in a separate universe parallel to the rest of the comic book world. It wasn't sold in comic book stores or bookstores but rather published by gay publishers, serialized in gay newspapers, and sold in gay bookstores. There have been a couple of creators who have been able to cross over to the mainstream, like Alison Bechdel (creator of Fun Home and Dykes to Watch Out For), but the vast majority of these comics are going to be lost even though a lot of it is very good. Even other cartoonists often don't know about queer comics because there were so isolated and removed from the traditional comic book world.

DB: You cover 4 decades, starting in the 70's. Was there anything that predated this decade that didn't make it into the book?

JH: I started the book at 1972 with Wimmen's Comix #1, with Trina Robbins writing about her roommate (who happened to be Robert Crumb's sister) in a story called "Sandy Comes Out." It was the first story about a queer person that was not a gag strip, not erotic comics, and not derogatory.

But really the first gay comics were gay male erotic comics. Tom of Finland was doing mail order distribution of his comics as early as the late 40's, I believe. A lot of erotic comics have been well archived by organizations like the Tom of Finland Foundation and The Center of Sex and Culture. My worry was that the literary queer comics were going to vanish, that there was no one looking out for that work. Especially with the gay publishers and the gay bookstores dying out.

DB: What were the challenges in compiling this historic archive?

JH: Certainly the fact that a lot of the material was out of print and that a lot of the creators were dead or had vanished was a challenge. Also, because there are so many different streams of this material; there was everything from the underground comix from the 70's, to the gay newspaper strips of the 80's, to the punk zines of the 90's, and now web comics. Each body of work required its own research process.

Luckily, I live in San Francisco where a lot of this material was developed. An old publisher of these comics, Last Gasp, is actually right around the corner from me. I was able to go through their warehouse and just rifle through and see what they had left. Also, a lot of the creators are around. Trina Robbins is my neighbor. I went up to Portland to talk to Andy Mangels and Robert Triptow who edited the Gay Comix anthology series. I've been doing a lot of work with Prism Comics, the non-profit advocacy group for LGBT comics, as their talent relations' chair, so I was lucky enough to have personal relationships with most of the people in the book.

We also have international work in the book, from Germany, Spain, France, Israel, some of which has been published for the first time in English. That material certainly presented obvious challenges. Looking forward, I'd love to do more about the web; that medium is exploding and opening up. It'd be wonderful to do a follow-up volume in five years with mostly queer webcomics.

DB: What has the response been like as it's just launched?

JH: A couple of weeks ago we did an advance debut in Chicago, we got some advance copies from the printer and it was the first time it was on sale. It actually hits the shelves in most places this week, the week of Comic-Con. The early buzz has been wonderful and gratifying. Everyone who has seen the book has been really positive about it. I've gotten push back here and there, of course. There was a blogger who was upset at the use of the word "queer;" he felt that it was a hate word. There are always going to be reactions like that.

Hopefully when the majority of people see this book, they'll be excited and hopefully amazed by the quality of this material. There's a lot of incredible stuff here that has escaped attention for too long.

DB: In compiling the material, was there anything you found that inspired you and your work?

JH: The bravery of the early queer comics is remarkable, and very inspiring. Mary Wings' Come Out Comix came out in 1973 and it's a pretty raw book. She told me she was 19 before she ever even heard the word "lesbian." She saw Trina's "Sandy Comes Out" soon after coming out herself and thought, "A straight woman shouldn't tell this story; it should be a lesbian." Then she made Come Out Comix in the basement of a radical women's karate co-operative and sold them for a $1 a piece by mail order. That takes some serious guts. Times have really changed, but at the same time you look back on the material from the 70's, from Wings and Roberta Gregory and others, then later coming out of the 80's with Howard Cruse and Gay Comix and that crew, and much of it is really brave, honest, and sophisticated.

I think now we're seeing similar work being done with trans identity. Christine Smith, for example, does a web comic called "The Princess" about a young trans girl. She's trying to show young trans kids that they're not pathological, that they're normal and can have happy lives in the same way that Mary Wings was trying to show young lesbians that they're normal and can have happy lives. It's a similar project across the generations and that's very inspiring.

Mind you, not everything in the book is celebratory stuff; it's also people looking at issues of racism in the queer community, the horrors of AIDS, partner abuse, all different kinds of things. There's some really powerful stuff and challenging stuff. The more I dug, that was what was most surprising, how many different points of view there were on queer realities.

DB: Speaking about generations, you've been in the queer comics scene for some time. How do you see the queer comic scene moving forward?

JH: The early battles were about basic visibility. Alison Bechdel talked about that when she created Dykes to Watch Out For; she just wanted to make lesbians visible. Twenty-five years later, that basic visibility isn't the issue any more. In a sense, that's the job of the mainstream comics industry now. The mainstream is including and assimilating queer characters, such as the gay Archie character and the lesbian Batwoman. But while it's now the mainstream's job to include and assimilate these characters, it remains the queer comics underground's job to continue to analyze and dissect and poke fun at queer identities in a way that is not appropriate for the mainstream to do. That needs to continue in the future.

Now that the traditional queer media ghetto of gay bookstores and gay newspapers is faltering, people who want to continue to make real niche material will find niche markets on the web. You can find audiences on the web in numbers that were unimaginable in the past.

At the same time, there's definitely more possibility for crossing over into the mainstream book market now.

There is more acceptance of graphic novels and the comic book form and certainly more acceptance of queer narratives.

DB: Why do you feel queer comics are important to the queer experience?

JH: Unlike film and television, which require a lot of money and collaboration and backing to do, comics is just you with ink and paper.

One person can create their own vision in queer comics and get it out there. That's really powerful. Queer comics tend to be quirkier, more challenging, and more ribald at times, because of their underground, DIY nature.

Another reason is that comics are a narrative form that's also visual; reading a comic about queer lives is different than just reading a book about queers. Young queers can look at it and can see themselves in it. And that's profound, that visceral interaction with a visual narrative.

DB: Why did you pick Chicago as the city for your advanced debut?

JH: This was the first year of CAKE (Chicago Alternative Comic Expo) and I wanted to have the book for the inaugural year. They were particularly interested in a good gender balance and queer inclusion for the show, which is something that a lot of people in the industry, even the independent comic industry, tend to gloss over. And when I found out Chicago Gay Pride was the next week, I decided to stay and do that event at Chicago Comics in Boystown. I had a great time in the city, did lots of cultural stuff. Saw Millennium Park, saw some theatre, including the hilarious Steamwerkz: the Musical. I had a blast; just walking the streets of Chicago was a blast. And not to be too gay here, but there are a lot of hot men in your fair city.

No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics hits the shelves at comic book stores this week, with a rollout at bookstores over the month. It is also available online at www.fantagraphics.com or you can stop into Chicago Comics, where it is currently in stock.

Interviewed by Danny Bernardo